Create a Console Server with a Raspberry Pi

UPDATE 9/6/2016: I’ve added an extra step I had to take when I added a USB hub to my setup.

If you want to skip my ramblings and go straight to the tutorial, click here

I’m in the wrong business

I have lots of options. In the technology field, I could do systems engineering, DevOps - I could do one of those cool new bootcamp schools and learn to be a data scientist. Or, I could leave behind this fast-paced world of technology and the constant bending of my mind to conform to a machine that only speaks in two digits and pursue a different area of work. Marketing, nursing, truck driving, carpentry, farming… All valuable and meaningful work, I’m sure. And some pay better than others, but I’m convinced none offer better profit margins combined with ease of getting a product to market than enterprise hardware sales.

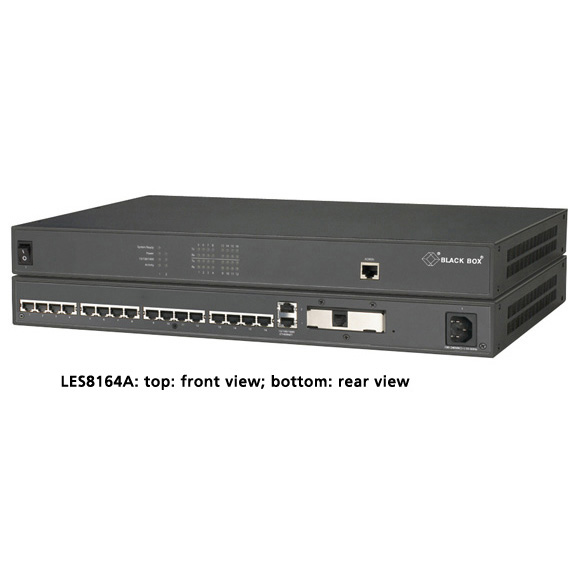

Why enterprise hardware sales, you ask? Please take a look at Exhibit A (the only exhibit I’ve put together), a Black Box LES8164A 16-port Secure Console Server.

It is a beautiful piece of hardware, for sure. Those clean black lines, the understated simplicity. You could almost call it minimalistic…in an IBM sort of way. And really, it doesn’t look that complicated, either. Yes, there are 16 ports on the back, but other than that, there’s only one button, for power. And if you were to look inside of it, you’d be even more amazed at how simple this box is.

I was just taking a picture through the vents on the side, but you can tell from the picture that there’s not a lot going on, at least nothing more than most low-power hardware. And that’s all there is to it. On the software side, it allows you to establish connections to serial devices that are connected to those 16 ports, via the server’s own IP address and a virtual port. For example, let’s say my Cisco 2911 router was connected and configured to use virtual port 5001. I would simply run telnet 10.0.0.2 5001, and the console server would forward all my traffic to the router, letting me connect to it as if I were directly connected over a serial connection. This is pretty cool. It also lets you do a few other configurations that are basically variations on that use case, but nothing crazy. Now, how much will this thing cost you?

Only the small sum of $1,805.85

That’s right, for more than the price of one of those 2911 routers, or even the price of a low-end rack server - things that actually do something - you can have yourself a pretty black box that forwards packets on to other devices connected to it. That sounds like a switch, you say. Well, you’re right, it’s not much more than that.

So why is it $1,805.85? My only guess for why anyone can get away with selling a console server like this for $1,800+ is because of who they’re selling to (enterprises). Because once you see that you can make something like this for $90 and 30 minutes of work (did I mention I spent a few days trying to setup the Black Box?), you might reconsider the industry you’re in.

Ah, the Raspberry Pi, a legend of computing. It has arguably been one of the most democratizing devices in recent computing history. It’s combination and well-designed ratios of power, cost, approachability, and size have made this the de facto standard for hobbyists, students, and enterprise workers like me who have had their eyes opened to just how cheap these devices are, and what you’re really paying for when it comes to enterprise silicon.

Anyway, enough rambling. Let’s build this thing.

Get a Raspberry Pi

Here is a Raspberry Pi 3 kit that makes setting up the Pi a lot easier. It includes the Pi 3, a case, power adapter, HDMI cable, a micro SD card with NOOBS pre-loaded (so you don’t need to download and format an SD card), and even a couple heatsinks (probably not necessary but cool to have). You can just get the Pi by itself, but it is way more enjoyable to get a kit so you can be up and running much faster.

Install Raspbian

First, we’ll need to install the OS. You should probably use the default distro for the device, Raspbian. It’s a Debian variant tweaked for the RPi that should have what you need for 95% of your use cases. There are plenty of guides on how to do this online, so I’ll let you figure that out, as it’s pretty straightforward anyway. And, if you use the RPi that I linked to, it will have NOOBS which makes it basically a one-click affair. After you’re up and running, and made sure you’ve sudo apt-get upgradeed your system, move to the next step, and the real fun.

Configure the network

This step is really optional, but I think a static IP would be your best bet in this case, unless you want to use something like a dynamic DNS client. Otherwise you’ll be left guessing the IP address for your console server.

Open up /etc/dhcpcd.conf, and add the below lines, replacing the #s with your actual address.

interface eth0

static ip_address=###.###.###.###

static routers=###.###.###.###

Setup ser2net

Note that the “router” is equivalent to the gateway, if you’re not actually plugged in to a router. Next, install the ser2net package. If you also want to use telnet to console into your devices, install the telnetd package

sudo apt-get install ser2net telnetd

Now that those are complete, we need to setup our /etc/ser2net.conf file. Learning the syntax and structure of the configuration file kind of feels like you’re learning another language or huge tool like Apache, but after you get a feel for it, it’s actually pretty straightforward, and for our purposes, there’s not a whole lot to setup. First, you’ll want to find what serial connections you have and where they are using dmesg.

dmesg | grep tty

[ 0.000000] Kernel command line: 8250.nr_uarts=0 dma.dmachans=0x7f35 bcm2708_fb.fbwidth=640 bcm2708_fb.fbheight=480 bcm2709.boardrev=0xa22082 bcm2709.serial=0xb65b0142 smsc95xx.macaddr=B8:27:EB:5B:01:42 bcm2708_fb.fbswap=1 bcm2709.uart_clock=48000000 vc_mem.mem_base=0x3dc00000 vc_mem.mem_size=0x3f000000 dwc_otg.lpm_enable=0 console=ttyS0,115200 console=tty1 root=/dev/mmcblk0p7 rootfstype=ext4 elevator=deadline fsck.repair=yes rootwait

[ 0.001335] console [tty1] enabled

[ 1.935233] 3f201000.uart: ttyAMA0 at MMIO 0x3f201000 (irq = 87, base_baud = 0) is a PL011 rev2

[ 329.653259] usb 1-1.2: FTDI USB Serial Device converter now attached to ttyUSB0

In my case, the key line is the USB Serial Device converter now attached to ttyUSB0. This tells me that a USB device (a Cisco style console cable) is connected on the first USB port on the RPi. ttyUSB0 corresponds to the device file in /dev/ttyUSB0. If you wanted to manually connect to this port, you could issue a screen /dev/ttyUSB0 which would open up a console session. If you did that, press Ctrl+a, then Shift+k to kill that session, otherwise you won’t be able to connect to it later via ser2net. After you’ve written down all the devices that are connected, it’s time to start filling out the configuration file. Go to the bottom of the file and add something like the following:

BANNER:banner:OnX Lab Console Server

port p device d serial parms srn

TRACEFILE:tr1:/var/log/ser2net/\p-\Y-\M-\D-\H:\i:\S.\U

4001:telnet:0:/dev/ttyUSB0:9600 8DATABITS NONE 1STOPBIT banner tr=tr1 timestamp

Let’s break this down.

- The

BANNERsection defines a banner message (like a motd) that you want to display anytime someone logs in. The all capsBANNERpart states you’re defining a banner. The next part after the colon defines the name of that banner (since you could show, for example, different banners for different connections), and part after the second colon is the actual banner message. Note that the message can be multi-line if you so please. - The

TRACEFILEportion defines a log file which will log everything that’s output and input into a session. This is an important thing to set up. Like theBANNERsection, the first part says that it’s a tracefile you’re setting up, the second part names it, and the third part is the actual file name and location. In my example, I put it under the/var/log/ser2net/directory, and gave it a name with some of the builtin variables ser2net uses. If you read the man page for it, you can see the full listing of options you can use. What I used in my example was: p: that device’s portY: today’s yearM: today’s monthD: today’s day of the monthH: the hour in 24-hour formati: the minuteS: the secondU: the _microsecond_ And there are a lot of other options, so you can setup your log files in whatever format makes sense to you.- Start off the actual device definition with the port number you want to use. After the first colon, you’ll specify the device. ser2net calls it “state”. Your options are off,raw,rawlp, and telnet. Telnet will actually work with both telnet and ssh, so I’m guessing that’s what you’re going to use most of the time. After the second colon, you’ll specify the timeout for that port, with 0 meaning disabled. After the third colon, you specify the actual device file that we grabbed using dmesg earlier. In this example it’s

/dev/ttyUSB0. After the fourth colon, you get to specify all the options. This includes the typical console settings like the baud rate, flow control, etc. Here we’re using 9600 baud, 8 databits, NONE to set no parity, and 1 stop bit. We also specified the banner name from earlier (and in the way the syntax works, you probably shouldn’t name any of your banners in a way that matches any of the device configuration options, to avoid confusing ser2net). Thetr=tr1tells ser2net which tracefile to use. The reason we’re explicitly naming this parameter, unlike the banner, is because you have several different options for the tracefile.trtells ser2net to log all data read from the device. You can usetwto log all data written to the device, ortbfor both data read and written. Note that you can use all of these options at the same time and write to three different files.timestampadds a timestamp to the tracefile. - There are a few other options that you can read about in the man pages, but the options I’ve used here are - I think - the most commonly used ones.

Now, we need to create the directories for the trace (log) files that ser2net will write to. We don’t need to create the actual files, just the directories it will write to.

mkdir /var/log/ser2net

We’re almost ready to test, but first restart the ser2net daemon so that it picks up on the changes we made

/etc/init.d/restart ser2net

Now we’re ready to test. Make sure your serial cables are plugged in to your device and the RPi. On another device, telnet into your RPi over the port you specified for one of your devices

telnet 10.0.0.20 4001

If everything worked, you should get the banner message you added to the configuration file, followed by whatever prompt you would normally get when directly connected to that server. To close out of it, press Ctrl+d, then ] (the right bracket). Now, let’s make sure your log file is being created successfully. Log back in to the Pi, and ls -l /var/log/ser2net to confirm the file is there. If you cat the file it should show everything you were seeing when you consoled into your other device.

Congratulations, you just build a console server, and saved approximately $1,700 in doing so. You might even get a pat on the back from your boss. Now go and secure your Pi.

The Raspberry Pi 3 comes with 4 USB 2.0 hubs, which is great, but I decided that I needed a few more ports as I would be needing console access to more than 4 servers at a time. I got an Anker 10-port USB 3.0 hub which is a slick little device. It’s well made, and the clear numbering on the side makes it easy to use in my case, where I would be communicating to people onsite where to plug in different console cables while I worked remotely. I pluggged the hub into the Pi, then checked dmesg to see if it recognized the hub. It gave me some errors like port1: unable to enumerate USB device and the key one being device not accepting address #, error -71. For some reason, the Pi wasn’t able to communicate correctly with the hub and its ports. After some searching, I found some options that worked for some people, but ended up landing on one that made the Pi use USB 1.1 (!). You use these options by adding them to the /boot/cmdline.txt then rebooting.

usbcore.old_scheme_first=Y- This appears to make the Pi use an older style protocol that uses a smaller initialization handshake with the device than what many newer devices use. It didn’t work in my situation.usbcore.use_both_schemes=Y- This should make the Pi use both the older (from the last bullet point) and the newer schemes, but this didn’t work for me, either.dwc_otg.speed=1- This essentially tells the Pi to operate at USB 1.1 (read: old school) speeds. I saw a lot of warnings about this, as it apparently can cause more problems on some devices, making Pi take forever to boot since it has trouble doing even basic communication with some devices. I tried the other options first because of this, but in the end, setting the speed lower made the hub work. It’s definitely a workaround, and could be problematic for other devices to connect (many people had problems getting keyboards and mice to connect while this option was turned on) but for my single-purpose device, it works for me. This also makes your ethernet port run super slow, as this setting also apparently controls the speed at which the port communicates with the motherboard. So if you need to transfer a lot of large files quickly, you might want to look to using another device in addition to this one.